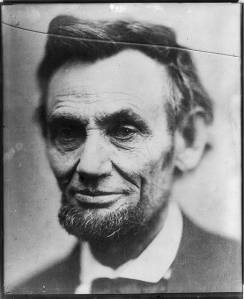

Do I really need to say this is not historically accurate? Probably not. But should you want to see where it came from, here you go.

The name of this blog is “Public History Goes Digital” for a reason. Today, public historians strive to reach as many people as possible and the internet’s seemingly infinite space and open accessibility makes it much easier. Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig discuss just this in their book Digital History. They state,

In the past two decades, new media and new technologies have challenged historians to rethink the ways that they research, write, present, and teach about the past.

One of the many benefits of living in this digital age is the direct access to so many historical documents and methods of sharing information. To quote Cohen and Rosenzweig again, “to those who previously had no easy access, online archives open locked doors.” People can be on a computer in Washington, D.C. and take a tour of a museum in Paris. They can compare photos of a street in the 1920s to what that street looks like now on their phone as they walk through that neighborhood.

But, are historians succeeding at reaching the masses and serving them well?

Sort of.

Rebecca Onion’s “Snapshots of History” laments how twitter accounts like @HistoryinPics share historic photos without proper attribution, external links, or detailed captions, yet are wildly popular, some even with upwards of a million followers. People love to see old photos, particularly of famous figures or events. So why do these informal, and often contextually inadequate, accounts speak to so many people when Rebecca’s own twitter account @SlateVault has less than 10,000 followers? She does essentially the same thing, but with much more text. Is that the problem? Despite their best events to slash their word counts on the web, are historians still overwhelming audiences with facts and knowledge?

Stephen Robertson accredits part of the problem to the blurred lines between digital history and digital humanities. He says that “efforts to extend the conversation about digital history beyond the digitally fluent […] are not helped by calling our work ‘digital humanities.’” Historians are so wrapped up in internal dialogues with their colleagues and with those already in the digital world that they sometimes exclude the audiences they want to reach. If viewers don’t care about a photo’s citation, they certainly don’t care if what they are looking at qualifies as one form of digital history or another.

So is that the key? Do we need to stop over thinking and simplify our methods of promoting accurate history? Well, no.

Long thought to be the last photo of Lincoln, this Alexander Gardner print was actually taken in February 1865. To read more and see the the actual last photos, check out this article.

True that people often want basic information, but there are times when they crave more and times when they need more. They should not have to be formally trained historians to find this information. Everyone knows to go to Google first, but do people know about how many fully digitized documents are on Internet Archive? What about Archive Grid or even the amazing collection of photographs at Library of Congress? These places shouldn’t be secrets. As a public historian and as a trained historian, I want people searching through these places, not pinterest, not other twitter accounts. I would even take Wikipedia over those sites because while that is also a collaborative effort, people tend to monitor it so carefully that truly outlandish posts disappear fairly quickly.

These fun history accounts, like @HistoryinPics, prove that people clearly want to learn about the past, but are they getting the full story? Are they even getting enough of the story?

Rebecca Onion brings up many valid points. These accounts should give credit where credit is due. These photos came from somewhere and belong to someone, so if the account updaters can find this information, they should include it. Hyperlinks mean that you don’t even need to actually say a photo is from the Library of Congress, you can just link to it within your caption.

More importantly, though, people need to know the context. The date, the location, the photographer, the publisher—this all informs the historical record and it just may change the story. Sometimes, the context behind the photo is even more interesting than the photo itself. Providing these details or a simple link to an outside source enables site visitors to discover the “joy of the historical rabbit hole,” as Onion so aptly puts it.

Just a nice 1937 photo of Stalin, right? Wrong. This is one of the many examples of Soviet purging. Nikolai Yezhov used to be in this photo beside Stalin, but was removed after he fell from Stalin’s good graces. Read more about this practice here.

But, realistically speaking, no matter how often or loud historians criticize these twitter accounts, they will not change their practices overnight. Instead, public historians should focus on improving their own digital history skills and increasing their audience base. Social media and the internet offer an incredible opportunity to advance history, so why are the historians not the primary ones advancing it?

Here is the most common photo of Clara Harris, one of the Lincolns’ guests on the night of the assassination. But is this the right Clara Harris?

As much as it may make historians cringe that only a handful of people view their posts when compared to @HistoryinPics, they should avoid pandering to that level of inaccuracy. We know better and we are better. So yes, cater to your audiences, to an extent, but above all, keep the information accurate (as best as you can) and flowing.

Find something interesting and share it. Say what it is, who it is, when it’s from, and then link to other information. That’s all that is really necessary. Keep it short and sweet, but tease the viewers with other information. Give them a white rabbit to follow and hope they fall down the rabbit hole like we all did.

Nice post! I like your concluding suggestions in the final paragraph. It’s basically the philosophy that led me to create @Every3Minutes, a feed that doesn’t give much information but gives enough to hopefully get broader audiences interested in the history of the domestic slave trade. More on my thinking is here.

LikeLike

Thank you so much. It means a lot to have someone in the field compliment my writing and thoughts. I just started following you and @Every3Minutes. That constant feed is such a great use of digital technologies to get people interested in history and I really enjoyed reading about your process for creating it. That is definitely the kind of thing I hope to encounter more as I embrace the digital world.

LikeLike

Hello Anna! I really enjoyed reading your article, especially since it presents an argument opposite of my perspective on Rebecca Onion’s piece.

Rebecca Onion’s article reminded me of our readings on sharing historical authority from “Letting Go?” our very first semester together. It seems that the question still remains: do historians have the final word or is their authority shared?

While I agree with Rebecca Onion’s argument that co-collaboration with public audiences can be a threat to the discipline due to the public’s lack of training in historical methodology (i.e. providing attribution, historical context, and resources), I do not necessarily agree with her scope and focus.

As Sydney skillfully pointed out in her blog post on this topic, Onion’s focus and presentation revolves around the @HistoryinPics twitter account whose purpose is to post historic photos for the public to enjoy the aesthetic value.

This is where Onion lost me as an advocate. After scouring the @HistoryinPics site, I was unable to find a statement of purpose, about page, or something similar that clearly states that the site seeks to be historically accurate. So, here is my question to you: if the site does not aim to present historical content in hopes of accurately educating the public, how can one fault it for something it is not created to do?

If you remember back to our class, Historians Craft, Dr. Breitman said with regards to book review that “one can critique a book for what it sets out to do, but not for what it is not meant to do.”

I think that this holds true to Rebecca Onion’s article. While it does bother me as a historian that @HistoryinPics does not provide the proper historical information, I do not think we can fault it for not doing so when that is not the site’s purpose.

I would even go a step further and say that @HistoryinPics may even provide a useful tool to inspire the public to become interested in history. As you pointed out, @HistoryinPics is more capable of reaching a wider audience than most historically sound sites such as @SlateVault. Thus, if a user becomes interested in an image or series of images from the @HistoryinPics, they may further research the photo which may lead them to the historically sound websites.

Do not get me wrong, as a historian, a little piece of my soul dies when the proper historical methodology is not used. But, chances are the admins of @HistoryinPics are not trained historians and they do not claim historical accuracy on their site. In the end, the Twitter account could act as the white rabbit for general audiences to follow that could lead to the rabbit hole that is a historically sound website. And just maybe, they will fall in and learn something new.

LikeLike

Pingback: Let the People Have Their Internet and Edit It Too! | Public History Goes Digital

Pingback: Apps | Public History Goes Digital

Pingback: Apps: The Future for Museums? | Public History Goes Digital

Pingback: Digital History…It’s A Wrap | Public History Goes Digital