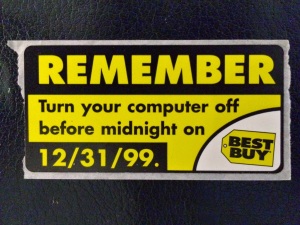

Remember Y2K? When people freaked out because they thought computers wouldn’t be able to handle the transition to the new millennium?

Or when we all discovered Google Earth and became fascinated (or terrified) by the potential to look at satellite images of our homes?

How far we’ve come from the days when having a cell phone was a big deal and when dial-up stopped being the go-to thing.

We take for granted all the advances technology has made. When I want to go somewhere, I go to Google Maps to see how long it will take and what’s the best route. When looking for apartments, you can type in the address and get a street view of the neighborhood without ever leaving your home.

And museums are now just beginning to take advantage of it.

As I mentioned in a previous blog post, Ford’s Theatre teamed up with Google to create a street view of their museum, so now anyone can take a tour even if they live across the globe and without the funds to travel to the U.S.

The launch of Google Earth and Maps meant that people could virtually visit anywhere. You want to see the Scottish Highlands but you’re in Oklahoma? Go for it. But now, we’ve moved even further.

The ability to digitally map a space means that theoretically we can digitize everything.

“The spatial turn represents the impulse to position these new tools against old questions,” as described by Jo Guidi in his article “What Is the Spatial Turn?” We can use these technologies in corroboration with historical documents to create accurate depictions of past landscapes or buildings or really, anything we want.

And now, you don’t even need to be at a computer to access these resources.

Te increase in mobile apps and technology brings us to an interesting point, particularly for museums. These institutions constantly seek out new ways to interact with their visitors and with an app, anything, any exhibit, any place can become interactive.

In his article “Listening to the City: Oral History and Place in the Digital Era,” Mark Tebeau says that “the mobile computing revolution offers tantalizing possibilities to archivists, historians, and curators interested in reaching broader public audiences.”

Tebeau discusses how Cleveland Historical is utilizing mobile apps to bring oral histories to the public. “Listening to human voices on a mobile device allows users to experience memory within the landscapes where the stories were lived” and thus, lets visitors personalize what they learn.

These apps also mean that museums are learning to relinquish some of their authority,

Collaboration is but one aspect of the digital revolution that has forced scholars to reimagine their relation to public audiences and the curatorial process itself. First, as argued above, the openness of the digital revolution has made knowledge production more democratic, challenging traditional power relations between scholars and their audiences.

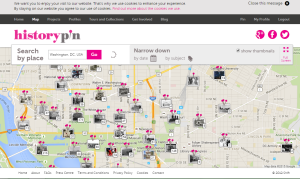

Apps like the Cleveland History Project, HistoryPin, or Chicago 00 let people choose how they want to learn history. If they want to be a recipient, they can. If they come across a place that interests them, they can pull out their phone and listen to a relevant oral history or scroll through historic photos.

Similarly, they can decide to give history. They can take a photo of an old building and upload it to HistoryPin for others to see.

Like John Russick said in his piece about Chicago 00,

Once created, the app could transform the current urban landscape into an historical excavation of the people and places that have defined Chicago over time. It could provide CHM with a new tool for sharing the city’s stories and help us connect the museum to the diverse audiences we hope to reach across the urban landscape.

Apps are the next step in the digital revolution and if they are able, museums should continue to pursue this technology. However, that doesn’t mean they should reduce their efforts in other areas.

Apps are often expensive to create and not everyone has a smartphone. So they should supplement museum’s current practices, not replace them.

It will be interesting to see how this situation progresses as the technology continues to advance.

Thanks for your post, Anna.

I absolutely enjoyed your flashbacks to Y2K, Google Earth, and other advances in technology. I particularly appreciated your How I Met Your Mother Image.

What I found particularly intriguing about your post is that I remember all of these events. And when your post caused me to reflect on those events I remember where I was and what I was doing, etc. I think this goes to show how history, especially digital history, has a clear connection to the past in terms of place and location. I think that Apps such as the ones you discussed enable visitors to tap into that connection to place, time, and location. If institutions further their use of Apps like these, I think they will be able to reach broader audiences and maintain the public’s connection to the past in terms of place, time, and location.

LikeLike

You definitely got what I was going for here! When I was thinking about apps and how much we rely on our phones, it made me think about how far we’ve come technologically and how much further we can still go. I always understood apps to be somewhat expensive and difficult to produce, but maybe that’s changed. Wouldn’t it be great if there could be an Omeka-like system for apps? Something cheap, standardized, and easy to use? Maybe it already exists, but if not, it could really help out those smaller institutions to reach larger audiences.

LikeLike

Thanks for a great post, Anna! I especially appreciate your note at the end about how mobile apps allow the public to engage with history in an instant. They don’t have to make decision to go to a museum, or even be in front of a computer, history is literally just a few moments away. I find that, armed with my smartphone, there is almost no reason to let something go unknown anymore – if there is a question I need answered, I can find it. It seems like the real question for historians is not necessarily whether they should go mobile, but how they can ensure that mobile content reaches the public. How can we publicize these tools to make sure they are accessible, that they become a viable alternative to pulling up a Wikipedia page? There seems to be an element of PR here, too.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Jen. I completely agree with you about how much I rely on my phone. I am on Wikipedia and Google constantly and now thanks to this week’s class, I have some new apps to check out.

You raise a good point about the PR element because museums really do need to find a way to market their products. I feel like that’s the common theme in this class: that museums are capable of producing high-quality digital media but they’re not as popular as they should be because people don’t know about them. Somehow, something about that needs to change.

LikeLike

Hey Anna!

I really enjoyed your post. I liked at the end when you said people “can decide to give history.” I think phrasing it in that way, particularly using the word “give” gets at the issue of authority that you touched on earlier in the post. I think that if we were to all change our frame of mind and realize that everyone has something to contribute rather than just collaborating something we’ve done research on, then we can start to embrace the emotional side of history and hear it’s different perspectives.

You show that apps certainly give us that potential and I hope in a few years down the line museums will all be using apps to enhance exhibits. Maybe then we can look back at a time when that wasn’t the case and see how silly it was just like how we view Y2K now.

LikeLike