That title is misleading, intentionally so. My digital history class is a wrap, not my foray into this aspect of public history.

Since starting graduate school, I have gained an incredible amount of digital skills (hopefully that can appease my parents who constantly told me that if I was to go into the museum field then I needed to learn to work online). From my digital public history internship at Ford’s Theatre to my new media course, I feel so much more confident in myself and my abilities.

Of course, that’s not necessarily saying too much. I had almost no faith in my skills before.

But now, I can build a digital collection, curate online exhibits on multiple platforms, standardize metadata, make appealing posters in InDesign, use Photoshop, edit Wikipedia, live tweet, write some basic HTML codes, pin items to Historypin and Pinterest, blog effectively, and a whole host of other things.

I have established opinions about how historians should use the internet to appeal to the largest audiences possible, learned what an archive actually is, and now see that learning can come in all different forms, like video games.

So yes, I have come very far in my brief time in D.C, but more importantly, I’m finally grasping exactly why people make such a big deal about the potential of the internet.

Technology has the ability to empower history in a way that print never could. It makes history accessible.

- A single online article or website can reach millions, or billions, of people; that is just not feasible in the physical realm.

- When I blogged for Ford’s Theatre, my posts had nearly 3,000 views. Unless I write the next bestseller (which funny how those usually aren’t history monographs), I’m never going to see those kinds of numbers again.

- Digitized archival material means that “to those who previously had no access, online archives open locked doors.”

- Digitizing collections is “about taking cultural heritage collections and changing them. Changing what we can do with them. Changing how we see them. Changing how we think about them., even the ones they don’t intend to display.”

- Mobile apps can “foster a new, robust relationship between the twenty-first-century communities we serve and the collections we care for.”

The web lets historians and museums branch out of their comfort zone to reach more people and to really utilize their collections or research.

As I said, in this past year, I’ve greatly improved my own digital presence and knowledge. However, many of the skills I gained were more thanks to the simplicity of the sites than any great effort on my part. I’ve come to realize that the digital world isn’t as scary as it once seemed. So many of the sites and tools that museums are now using (or should be using) are really easy to learn and that’s the beauty of the internet: anyone can participate.

But, it’s a double-edged sword.

The fact that anyone can contribute, collaborate, or view a museum’s site means that they can also judge it.

Crowdsourcing projects, like Wikipedia or Transcribe Bentham, have led to a sense of entitlement among internet users. And Paul Ford sums this up in the great question of the internet age: why wasn’t I consulted?

So what this means is that entering the digital age is harder than it sounds.

But that doesn’t mean progress should stop.

Just the opposite in fact.

Rebecca Onion’s diatribe against twitter accounts like @HistoryinPics are worthwhile to note, and I agree with a lot of her points, but I also can see the other side. Instead of railing against the practices of those who are more successful and popular than us, we should try to improve what we are doing.

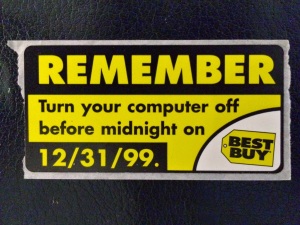

Every year as new technology becomes available, we as historians and museum professionals must keep abreast of the changing times. We are often so consumed with playing catch-up that we miss new opportunities to be innovators. We get complacent in what we are doing and think that, “well, I’ve learned how to use the internet, I don’t need to go further,” but that’s irresponsible of us as public historians.

The digital world is not going away; it is much too deeply entrenched in our society to be eradicated. Thus, digital history is not going away.

This is good news. According to Cohen and Rosenzweig,

In the past two decades, new media and new technologies have challenged historians to rethink the ways that they research, write, present, and teach about the past.

So just imagine what could happen in another two decades.

I’ve come so far since I learned basic keyboard shortcuts to copy and paste or reopen recently closed tabs. I’ve advanced to a point where I feel comfortable in the digital world. I can speak about it intelligently, offer advice, make recommendations, complete projects, and feel confident that I can do all of that well.

If Oscar Bluth can create and run a website while in prison, then surely I can keep this blog up while in grad school. Right?

Now it’s just a matter of maintaining this confidence. Life (read: grad school) gets in the way and time to explore digital technology falls to the wayside, but that has to stop.

I need to keep learning and seek out opportunities to expand my skills.

So to bring this post back to its title, no, the world of digital history is not over. We have not learned all there is to know.

It’s not a wrap; in fact, it’s just the beginning.